There is so much technology woven into our modern lives that some things appear almost indistinguishable from magic.

Wave your hand at your TV or game system, and it recognizes you, greets you by name, and brings up the content and applications that are part of your personal profile.

After a recent software upgrade for my phone, I turned it on in the next morning.

“Good morning, Greg!” it said. “Is this where you live?”

I’ll admit that, like it or not, I have become an information systems-augmented mind. In the middle of conversations, or when engaged by other media – like movies, news or sports – I’ll turn to Google, or to the aforementioned creepily inquisitive phone, and either find information to give me context or fact check what I’m hearing.

With all this magic swirling in our air, I find myself wondering if anyone has devoted any thought, during the years upon years of strategizing, designing and building it, to whether all this technology is beneficial for us, the human beings.

I think about this a lot, and more and more frequently, I find myself concluding that we are collectively just not that concerned about it.

We have tech for tech’s sake. We do these things – create these technical miracles – because we can, not because we have examined their effects on us.

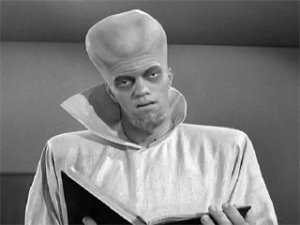

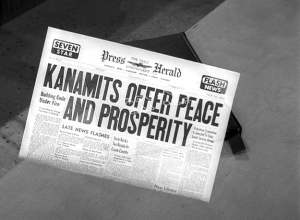

It recalls the old ’Twilight Zone’ episode about a race of Aliens that come to Earth, with what we assume are friendly, altruistic motives. And we continue thinking this until we discover their ‘bible’ – “To Serve Man” – is not a spiritual guide, but rather, a cookbook.

I see only parallels – our technology is assumed to be benign, but may be hiding deeper, darker outcomes.

There are lots of subtle examples. I could write a book on the adverse cognitive effects of ubiquitous text, e-mail and social messages interrupting activities that formerly required absolute intellectual focus. Reduced analytical horsepower and declining worker productivity are subtle, borderline subjective impacts, but one recent area of concentrated technological growth provides a perfect example of capability ignoring the potential insights of psychology and cognitive science.

A recent Washington Post story reported on the automotive industry’s drive to fit cars with Heads-up Displays (HUDs) to complement the in-car telematics and navigation systems.

The manufacturers claim that these systems, which project information and images into the driver’s field of view, will increase vehicular safety by reducing distractions. Cognitive science and experience seem to point to exactly the opposite. I will give massive credit to the authors of this Post piece — Drew Harwell and Hayley Tsukayama – for failing to accept this message without highlighting the significant evidence pointing to the contrary.

“Our military fighter pilots use it – it must be safe…” Actually, the military has documented something they call ‘attention capture’ – a cousin to the phenomenon known as ‘target fixation’, where a vehicle operator stops seeing anything outside the most colorful visual input – and then the vehicle goes in the direction where the operator is looking. As a result of these findings – information on the pilot’s visual field reduces pilot focus and performance – the military is rapidly de-emphasizing use of these systems.

Simple instrument displays are just the beginning – one vendor wants to project a ‘virtual car’ into the visual field so you can follow it, rather than the customary GPS arrows. Another, the Skully motorcycle helmet, wants to project this kind of information on the inside of a motorcycle helmet visor.

I consider myself expert in the area of performance motorcycling – anything which introduces even a millisecond of cognitive delay – “…is that ‘object’ real or projected?” – will adversely affect rider (or driver) performance.

Too many inbound information sources like texts and tweets want to distract you from getting tasks accomplished. In vehicle HUDs and telematics systems want distract you and get your vehicle crashed, and you, by inference, killed.

Technology is a wondrous thing, but only when its products are guided by wisdom of designers that understand what human beings really need. That quality of what I’ll call informed design has been all too absent in the last dozen or so years. We continue to do things – to push the boundaries of technology — because we can, not because we’ve done deep thinking to see if it’s really a good idea.

So the next time you pick up some new, shiny electronic thing, detach yourself for a minute and consider.

“Is this thing here to help me, or to eat me?”